Introduction

by the Leo Katz Foundation

Atelier 17 was an important print-making group that began at the New School of Social Research. Leo was a teacher and active print artist at Atelier 17 from its inception. He co-directed Atelier 17 when Stanley Hayter was traveling or working in France.

"Atelier 17" by Leo Katz first appeared in Print, America's Graphic Design Magazine, Jan-Feb 1960. This poignant article documents the philosophy, craft and comradery that was common at the Atelier 17, along with the sad closure of its doors in 1955.

Images indicated with * accompanied the original essay.

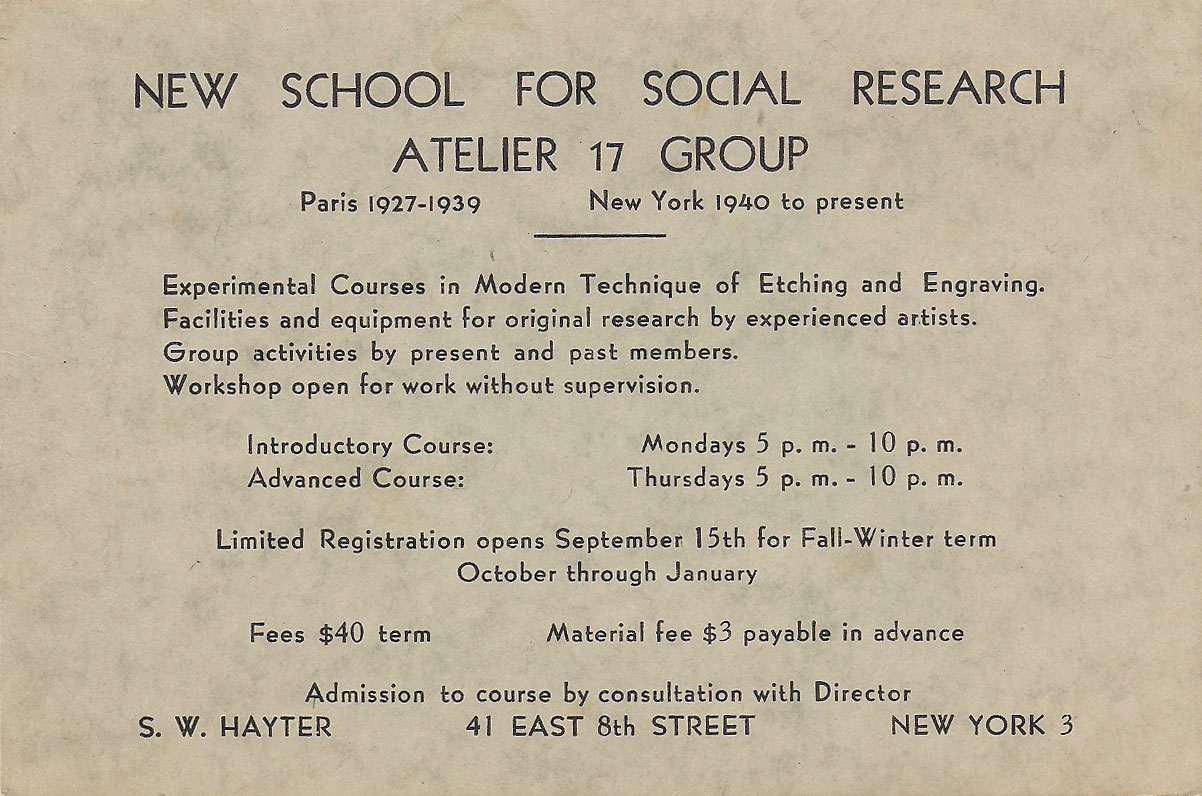

Class Flyer

Class FlyerAtelier 17

by Leo Katz

Though small in size, the studio's contribution to engraving and many other art forms - was enormous.

Recent events shocked us for a few days out of our post-sputnik complacency, and made us aware again that something vital is missing in our educational and cultural life. So far mostly quantitative remedies were suggested: more dollars, more classrooms, less high schools, etc. Yet until four years ago we had in New York a little place which could have taught us valuable and very much needed lessons. It was the Atelier 17.

In order to explain this statement we must realize that it contains several facets: 1. We have to look quickly through the history of the graphic arts to find out where the Atelier 17 fits in. 2. We have to enumerate the many technical contributions made by the Atelier. 3. We have to consider the psychological, philosophical and personality angles as a basis for those contributions.

Leo Katz at an Atelier 17 Press

Leo Katz at an Atelier 17 PressHistorical Background

The urge to engrave lines for symbolic or magical purposes can be traced back to prehistoric rock age. During the late Middle-Ages in Europe fine, engraved and (later) etched ornaments were made on helmets and armor, without any intentions of printing. In a way, the Summerian and Babylonian cylinder seals were probably the oldest known forms of printing into clay. Real printing was invented in China first. (A newspaper celebrated in Peking in 1909 the thousand-year anniversary.) Masters of the Renaissance introduced the printing of engravings on metal plates (copper) on paper. North of the Alps engravings rivalled woodcuts as the principle broadcasting system of ideas (in preparation for the Reformation). At that time man’s mind turned toward the exploration of the world of the “here and now” and toward the new importance of man’s personality. After centuries of gothic dreams of another worldly, ideational direction the eye and the heart had become hungry for a sensate worship of nature. Almost over night art fell in love with life. In this thrilling adventure engraving shared enthusiastically in the communication of this new vision and its discovery of new realities. Schongauer loved form without sacrificing the song of linear melodies. Veit Stoss in his prints was more expressionistic than in his sculptures, whereas Duerer used his single and multiple lines to simulate tactile form experience. At times he engraved with an intimate precision of living details, hardly ever achieved by photography four centuries later. He knew how to combine this descriptive passion with a Faustian depth. He also discovered how the fine burin lines condition they eye to see things much bigger than in print. A painting would have to be much larger.

The same passion for form we find South of the Alps in Manegnas engravings. However, in certain prints he uses lines as lines, pure and functional. This great pioneering spirit was soon lost after Marcantonio Raimondi’s success with his engraved copies of Raphael’s frescos and other famous paintings. Centuries followed when engraving degenerated into a tool for reproduction, illustration, invitations and such.

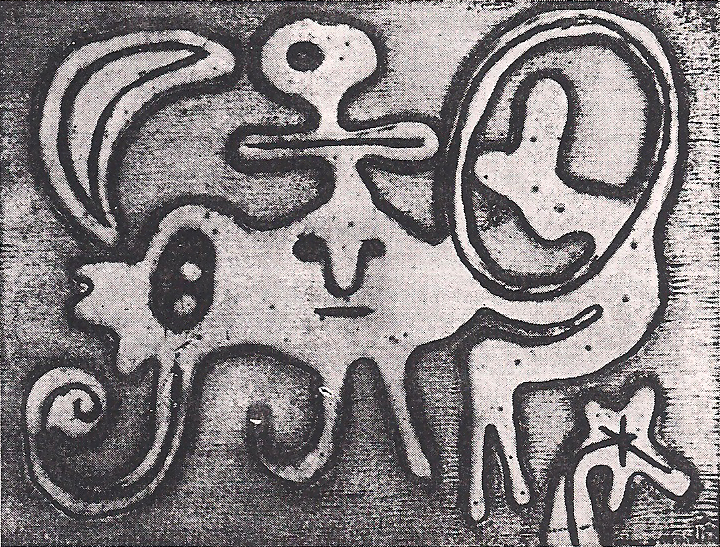

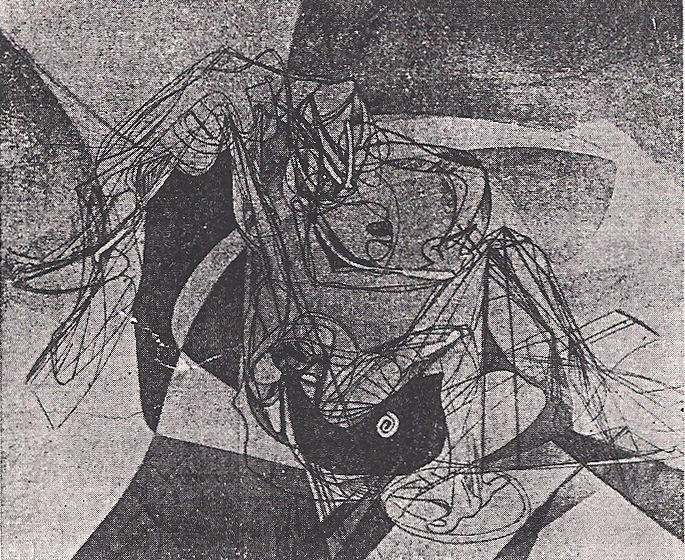

"Femmes et Oiseau Devant La Lune", Etching, 1947, by Joan Miro.*

An Art Nearly Dies

Etching, introduced by Duerer as the new chemical answer to the new spirit, reached its whiteheat of creative intensity in Rembrandt. Later it had interesting revivals by artists like Goya and Whistler. Finally, when the industrial era arrived, the growing demands for illustrations and reproductions were rapidly swallowed up by new photographic and mechanical methods. Engraving as an art was buried and etching, without contact with vital modern art problems, was ready for the funeral. Suddenly, a strange man appears, opens the coffins and says: “Rise, I see in you much life that never lived” and behold the dead E and E’s open slowly their eyes and walk away to lead the living.

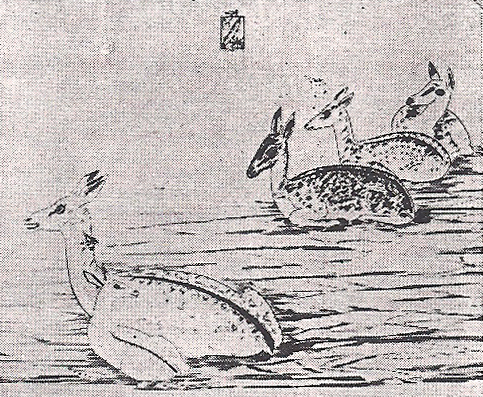

The man was Joseph Hecht (1891-1951). Probably the first one since Mantegna to search for the power and variety that lies in the natural qualities of the burin, he produced masterful engravings which show a whole vocabulary of a burin lingo from long gliding lines to short moves, on and on digging, plowing, stabbing, kicking wedgelike little movements or a pizzicato of points. He is either unrealistically descriptive (see illustration) or surrealistic long before surrealism was officially accepted.

The second act: Hecht meets Hayter. Stanley William Hayter, born in London in 1901, Welsh ancestors, an artist, son of a painter, trained as chemical engineer, 1922-1925 employed by the Anglo-Iranian Oil Co., in Persia absorbed all he could until he was able to make a plate together with Hecht without losing his own identity. In 1927 Hayter opened a studio (Atelier) in Paris in the Rue Campagne Premier. The number happened to be 17. Artists of many calibres and nationalities came to this place driven by creative curiosity. Thus the place became known as Atelier disept (Studio 17). Picasso, Miro, Giacometti, Max Ernest, Kandinsky, Tanguy, Vieillard, Calder, Vieira da Silva and other outstanding artists experimented and exchanged experiences and ideas there.

In 1940, the Atelier, being on Hitler’s black-list, moved to New York. In 1950 Hayter reopened the Paris Atelier and moved in 1954 to the Imprimerie Paul Haasen. The New York Atelier continued under the leadership of Karl Schrag, Harry Hoehn, Terry Haas and Peter Grippe who left 1954 to teach at Brandeis. I was back in New York and Bill asked me to take over, and so I was, for the third time, director of the Atelier. The first time in the summer of 1946 and the second time in ’49, both times during Bill’s trips to Europe. September, 1955, I had to leave and all efforts to find an acceptable substitute failed. The detailed story could easily fill a book. On September 7, 1955, the Atelier was closed. The Paris Atelier is still going strong and another branch was planned for London.

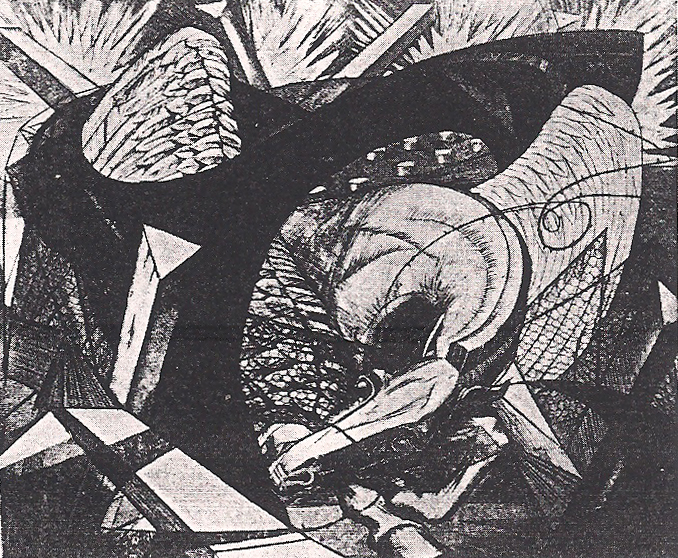

"Sol y Luna", 1945, engraving and soft ground etching by Mauricio Lasansky.*

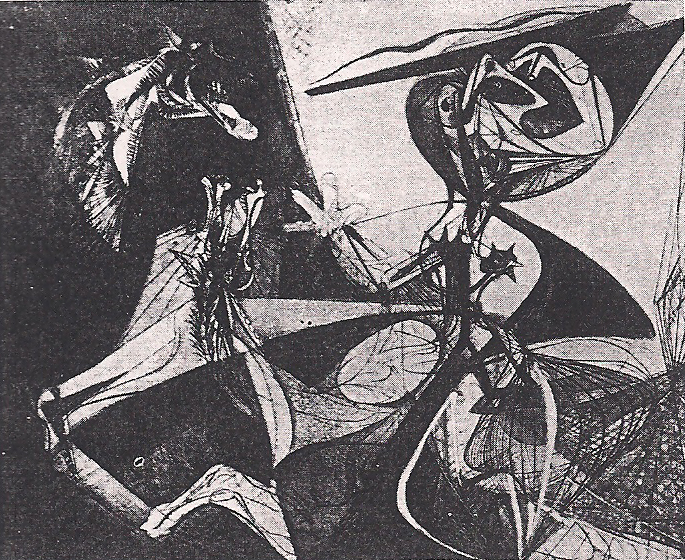

"Cronos", engraving and soft ground etching by S. W. Hayter.*

Technical Story

For detailed description of the technical procedures and contributions that developed in the Atelier 17 I recommend: New Ways of Gravure by S. W. Hayter (Routledge & Kegan Paul Limited, London 1949). For less complete material see Etching and Engraving and the Modern Trend by John Buckland-Wright (Studio Publications 1953) ; also, Atelier 17 Catalogue of the Fourteenth Exhibition of Prints by members of the Atelier 17 Group, Laurel Gallery 1949, (Wittenborn, Schultz, Inc., NY) Page 8, S. W. Hayter article, many illustrations. Finally Graphis magazine, Vol. 10, 1954, No. 55, Page 394. (It is interesting that most of the illustrations were from prints made at the New York Atelier.)In this article I can only present a simplified list of the different techniques taught and applied at the Atelier.

Line Engraving: Cutting into copper with a well sharpened burin is to me a noble experience, whereas a zinc plate gives me an “ornery” or mean response. The purist Hecht approach was continued by Hayter and exclusively by Vieillard (unique effects), in New York by Christine Engels (Mrs. Rubin), Sue Fuller, Lilly Asher, myself and others. I am still in love with this tool. Lotte Jacobi arranged for a fine exhibition in her gallery of line engravings by Hecht, Hayter, Vieillard, Courtin, Katz, Peterdi and Kett. In order to understand the intoxicating quality of engraving, one has to realize that every technique works in two directions. One is towards the effect on the beholder and the other is towards the effect it has on the artist. Michelangelo said: “Oil painting is for women and monks, fresco is for men.” What he meant is that in oil painting you can be careless or change your mind and paint over it. In fresco you are responsible for every brushstroke, changes are practically impossible. Engraving is like fresco. It makes a man out of you.

Etching: A copper plate, or zinc (Duerer worked with iron) is covered with an acid resistant coating. A drawing is scratched with a steel needle into the ground exposing the metal. Acid will bite, in those places, more or less deep grooves according to the time and the acid used. At the Atelier we used both, hard ground and soft ground etching. Soft ground is hard ground mixed and softened with grease. It permits different materials, gauzes, silks, nylons, laces, wood, wrinkled paper, etc., to be pressed through to the metal. When removed from the plate acid bites exciting textures into the plate. Instead of steel needles one can draw into the ground with matches, pencils, toothpicks, etc.

Aquatint: The plate is dusted with rosin powder. When carefully heated the rosin grains adhere to the plate and the acid bites around them or between, thus creating a more or less opaque tone.

Liftground: Ink mixed with non-drying ingredients like glycerin, syrup, gum Arabic or green soap can be used to paint, draw or transfer to the plate. When dipped into liquid ground and dried, a warm water bath will lift the ground off the drawing. Acid does the rest.

The Grible Method: Effectively revived by Abe Rattner. Different shaped points are hammered into the plate. In my “Ophiuchus” plate I used drills for the stars (points) and produced a milky way effect with a stiff stipple brush on soft ground. All those methods mentioned above belong to the “Intaglio” group. Scraped surface effects, beautiful used by Anna Rosa de Ycasa, Enrique Zanartu, Fred Becker and Kilstrom (all in New York).

Mezzotint: Plate roughened with rockers or roulettes to print black. Lighter parts brought out by burnishing. Grinding the plate with Carborundum can give similar effects. Planning with a coarse stone will produce printable tones. All those last methods belong to the group of Planigraphic Impressions.

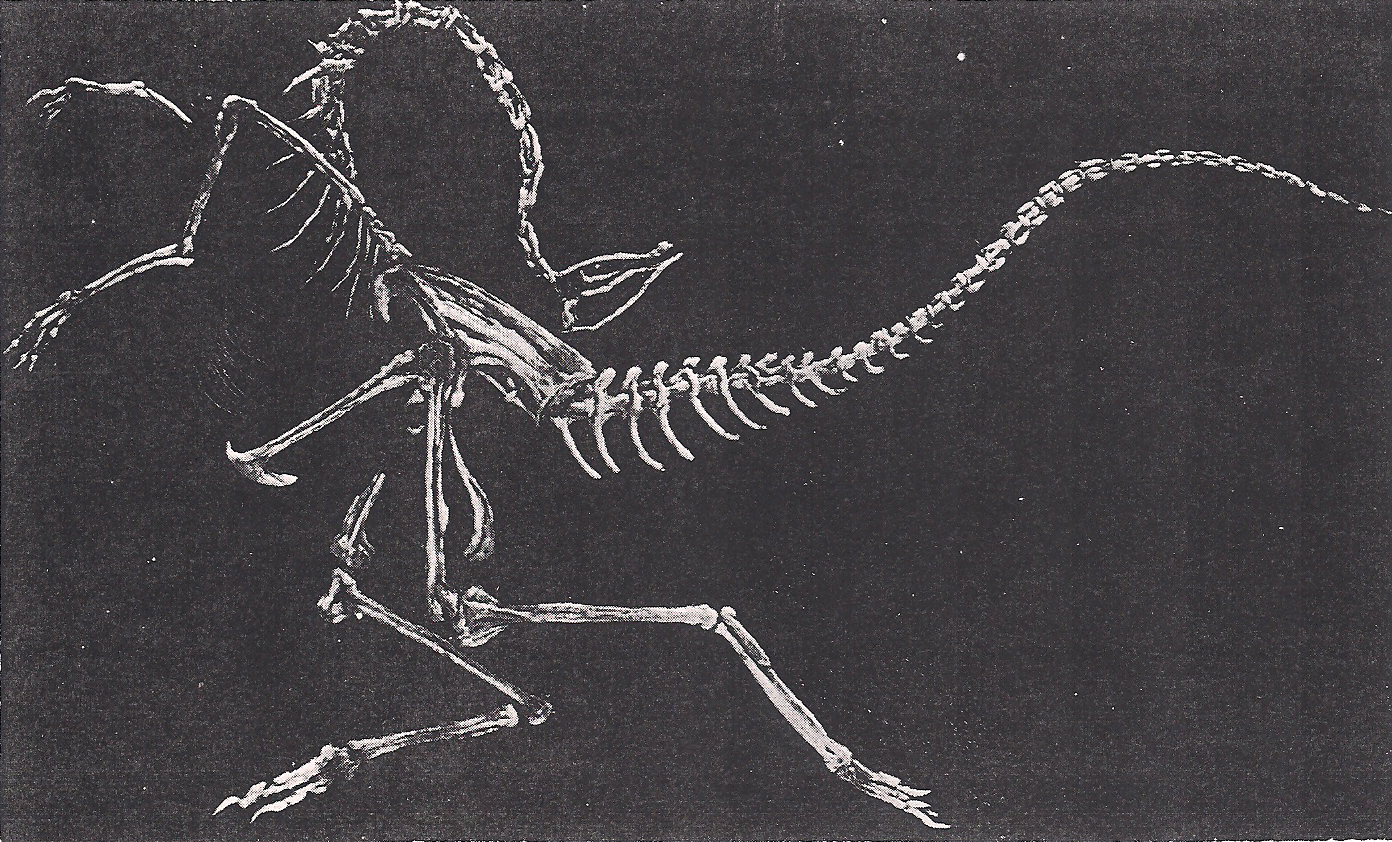

Color Offset: Using rubber, gelatin or another plate, glass, stone or plastic in combination with black intaglio print, a ticklish procedure. Intaglio prints in reverse, offset reverse twice and prints in the same direction as original. Fred Becker and Alice Mason made interesting prints with several color plates with utmost precision in registration. A voluntary slight shift in registration was used by Karl Schrag to suggest vibrations (“Night Wind”) or by Sari Dienes and Dorothy Dehner to give an illusion of relief. In 1946 Hayter used silkscreens to transfer three to five layers of transparent color to the surface of an inked intaglio plate. (see “Cinque Peronnages” three colors and “Falling Fugure” five colors). It is unlikely that anyone could make a list with any claim of completeness. Many things were tried then dropped. Some of them may suddenly reappear. A list of Paris experiments of recent years is not yet available. The last plate I printed just before the closing of the Atelier in New York, was the “Struthiomimus” entirely drilled with dentist burrs on a flexible shaft, approximating a dentist’s drill. A strong relief of bones (to give real “Totentanz” effect) was achieved on a very heavy paper by Douglas Howell. Hecht, Hayter and others used heavy scorpers by hand to give relief to small areas. Occasional experiments of printing on plaster of paris were combined with relief effects.

"Ophiuchus," 1950, engraving and soft ground etching by Leo Katz.*

"Struithiomimus", 1945, dry burr engraving in color by Leo Katz.*

Philosophy, Psychology, Personality

Many people forget easily that innumerable cities in Europe and in America never produced great basic ideas or a genius like Dante, Michelangelo or Beethoven. None of the giants of the Renaissance was born in Rome or Milan while Florence and vicinity produced an unusual number of supermen. In recent times Vienna and Paris were centers of creativity. The Atelier 17 proved that a little studio, occupied by a few artists utterly devoted to creative work instead of to money can become an island from which new methods, new approaches and much stimulation can burst forth to influence the graphic arts from Germany to Japan.

What is the secret of this place? It starts with “Bill” Hayter’s personality. A wiry shortish figure, a physiognomy that looks somewhat like Field-Marshall Montgomery or at times more like a suggestion of Napoleon (without the pompousness), a magnetic presence, charm, humor, irrepressible energy, sparkling intellect, a brilliant teacher, all this adds up to a human dynamo that attracts people from all over the world. (Buckland-Wright writes in his book: “Hayter has probably had more personal influence on the course of engraving than any artist in the history of the art.”)

When he moved to New York he started work in a rather small top floor studio at the New School for Social Research. He had to share the place with L. Shanker who taught woodcut on certain evenings. Later he moved to a larger loft on 8th Street, between Broadway and University Place. When this section was torn down, the Atelier found another loft on the Ave. of the Americas near the corner of 14th Street. A larger geared press was added to the smaller one which Bill started with at the New School. Not a penny was ever used for appearances but everything necessary was available.

The atmosphere was one of cordial informality unless someone was careless or inconsiderate in which case no one looked forward to “getting hell” from Bill. Everyone called everyone else by his or her first name. Everyone was expected to share ideas, results of experimentation. Bill was always a perfect example of bigness and generosity when it came to sharing. Giving became more important than taking, although there was practically never any goody-goody talk on such subjects. One of the most valuable memories takes me back to the little studio at the New School. Andre Racz (from Rumania) had just finished his Perseus plate. Lasanksy (from Argentine) was there and a few others including myself. Someone cut the paper, another prepared the blankets. One turned the spikes and I held the blankets stretched.

Atelier 17, photo by Leo Katz

An Ecstatic Appreciation

We had forgotten whose plate it was and I felt surely within half an inch from heart failure. When finally someone lifted slowly the paper from the plate we knew we were looking at a print the like of which no one had ever seen before. The freedom to follow boldly one’s artistic intuition was taken for granted. The search for inherently graphic realities in a print took the place of the plain descriptive realism of the past. There existed an almost ecstatic appreciation of the moment when hitherto unborn images were pulled from their invisible world of possibilities into the world of visible relativity. The study of the unexpected or accidental was considered as important as the respect for the discipline. As a matter of course, a new technique had to be found for each new approach. Thus the usual idea of one technique just being good or bad became meaningless. Equally meaningless was any attempt to divide the creative process into independent areas of mind separated from matter or visions, ideas or emotions flirted across a vacuum with technical tricks. Visions, emotions without proper technical expression are invisible and a technical performance without its nuclear center of emotional, intellectual or visual power is like a soul-less body. Bill fought with great intensity against this ignorance of the interdependence of technique and idea.

As to the members of the New York Atelier they were of many nationalities, of many different types and temperaments. Almost all European countries were represented and some from other continents. They also represented different isms, styles and philosophies. Here is a list of some of their names: Fred Becker, Letterio Calapai, Marc Chagall, Minna Citron, Ed. Coutney, Worden Day, Werner Drewes, Salvador Dali, Christine Engler, Sue Fuller, Peter Grippe, Jose Guerrero, Terry Haas, Ian Hugo, Leo Katz, Harry Hoehn, Mar Jean Kattunen, Kenneth Kilstrom, Alice Mason, Matta, Miro, Matrinelli, Seong Moy, Maria Martin, Le Corbusier, Lasansky, Lipschitz, Ryah Ludinis, Gabor Peterdi, Andre Racz, Abraham Rattner, Anne Ryan, Carl Schrag, Kurt Roesch, Alfred Russell, Ives Tanguy, Pennerton West, Louise Nevelson, Andre Masson, Joseph Presser, Anna Rosa de Ycaza, Enrique Zanartu, Sam Kaner, Doris Seidler, Lilly Ascher, Lotte Jacobi, Larry Winston, Chaim Koppelman and many, many others.

"Cinq Personnages", 1946, engraving, soft ground etching, color offset by S. W. Hayter.*

"Pegasus", 1945, engraving, soft ground etching by Leo Katz.*

Money Would Have Helped

Of course they were not all there at the same time. There was usually working space for 10 to 15. But the whole studio was a monumental proof for the fact, that it is not money, appearance, size, or “the customer is always right” attitude, that counts. All that may be essential in business or politics, but creative and cultural problems are of a different dimension. The Atelier was never a money-making proposition, and once in a while, with rising costs and fees kept at a minimum (so not to exclude the gifted but poor members) a financial shot-in-the-arm would have been welcome. Usually well meaning people were immediately suggesting to increase attendance, arrange for parties, raffles, exhibitions, receptions, entertainment, in other words the “bigger and better treatment.” It took an iron determination not to give in. And so the Atelier stayed small but its influence grew and stimulated remarkable changes in other territories like lithography, woodcut and even in painting.

Speaking of this influence, I would like to point out another overlooked observation. Most people are impressed by almost any majestic galaxy of famous names. In reality some of the finest contributions were made by lesser known members. A Chagall for instance was first of all interested in etching another fine Chagall and Dali, another Dali. Their styles were established. Some of them had at times neither sympathy nor understanding for other work in progress. Often a relative newcomer had more to give because he was not a slave of his own reputation. I remember one evening when Sue Fuller came to work armed with a bottle of Karo syrup from the A&P to experiment with liftground. Next to her sat Andre Masson, a leader in the surrealist movement which at the time was at the peak of its prominence. He became interested and Sue showed him what she found out through her own efforts. Mason made some gorgeous Balzacian heads with her syrup.

Of course, I do not want to say that meeting some of the great masters of modern art is not important for a young artist, if for no other reason than the fact that famous people are usually so much easier to get along with than bloody beginners. All in all, many people believe that having had the Atelier 17 in New York has certainly been a strong factor in making this city the art center of the world. To me it was a tragic day when, at Bill’s request and with the wonderful help of Harry Hoehn, George Ortman, Larry Winston and others we had to dismantle the presses, to pack and move day and night in a record-breaking heatwave, and to send out a press statement on September 7, 1955 that the Atelier 17 in New York was closed.

"Deer", engraving by Joseph Hecht.*

Prints ︎︎︎

© 2026 Leo Katz Foundation

lwadge@att.net | P.O. Box 292, Old Lyme, CT 06371

© 2026 LKF